The Israel-Iran war was highlighted by the U.S. strikes on three of Iran’s main nuclear facilities; Fordow, Isfahan and Natanz. The Operation Midnight Hammer involved a 36-hour round-trip mission that marked the first operational use of the 30,000-pound bunker-buster bomb. A total of 14 such bombs were dropped on hardened underground targets, alongside 30 cruise missiles launched at the Isfahan facility, signalling a coordinated and high-risk precision strike. The operation represented a dramatic escalation in the long-standing shadow conflict between Tehran and Washington. In the hours that followed, Iran launched retaliatory missiles toward Israeli air bases and U.S. assets in the Gulf, triggering further air defences and drawing in regional actors like Hezbollah and Iranian-backed militias in Iraq and Syria.

Israel's Iron Dome and David's Sling defence systems intercepted most incoming projectiles, but several key military sites still sustained damage. Civilian life across Tel Aviv and northern Israel was briefly disrupted, with air raid sirens and temporary blackouts marking the intensity of the exchanges. On the Iranian side, satellite images showed widespread damage to enrichment centrifuge halls, significantly setting back Tehran’s nuclear ambitions, according to initial IAEA assessments. While the war lasted only 12 days, the political and strategic aftershocks continue to reverberate, raising fundamental questions about the future of deterrence in the Middle East.

Strategic Damage Assessment

Fordow

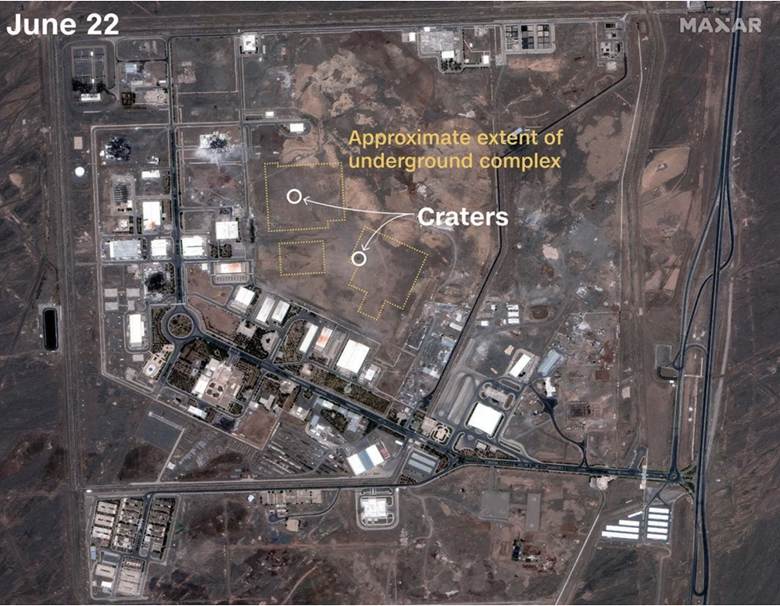

Fordow, one of Iran’s most important nuclear enrichment sites, is believed to be built 80 to 90 meters underground. The U.S. strikes used bunker busters to penetrate the mountainous terrain, creating at least six visible craters along the ridge covering the facility. Satellite imagery shows significant physical disruption, including grey ash discoloration and craters directly above enrichment halls. According to IAEA Director Rafael Grossi, there was a “direct kinetic impact” on the facility. However, the full extent of internal damage remains speculative due to the facility’s depth and Iran’s restricted access to international observers.

Despite Iranian officials initially downplaying the attack — calling it "superficial" — debris patterns and recovery vehicle activity suggest substantial damage. Given that Iran’s centrifuge cascades are sensitive to vibration and require stable environments, even indirect shockwaves could possibly render large portions of Fordow's infrastructure inoperable.

Natanz

Targeted during Israel’s opening salvo on June 13, Natanz houses both above-ground and subterranean centrifuge halls. Six surface-level buildings and three underground structures were damaged in this first wave, with IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) confirming that the site's electrical infrastructure had been severely compromised. The loss of power may have caused chain damage to sensitive equipment underground.

Subsequently, the U.S. B-2 bombers dropped two bunker busters on Natanz, while 30 Tomahawk missiles struck both Natanz and Isfahan. Satellite imagery revealed two new craters directly above underground enrichment zones. Analysts remain cautious about the full scope of damage but agree that these attacks disrupted Iran’s ability to enrich uranium.

Isfahan

Isfahan is Iran’s largest nuclear research complex, long suspected to be central to Iran's nuclear weaponization efforts. It was built with Chinese support in the 1980s and staffed by over 3,000 scientists. Satellite imagery after the strikes shows at least 18 destroyed or partially damaged structures, blackened terrain, and widespread rubble.

U.S. attacks also targeted nearby tunnel networks critical for secure transportation and concealment. Of the four known tunnel entrances, satellite images show three to be collapsed and backfilled. Reports suggest this could significantly limit Iran’s capacity to safely move fissile materials or scientists between sensitive sites.

Fallout and Diplomatic Consequences

On July 2nd, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian signed a law halting cooperation with the IAEA. This move followed Iran’s parliamentary vote to suspend all collaboration with the UN nuclear watchdog, accusing it of enabling Israeli targeting by sharing site intelligence — an allegation IAEA firmly denies. Pezeshkian’s administration has directed Iran's Atomic Energy Organization and Foreign Ministry to implement the law immediately. The breakdown of monitoring further obscures any assessment of Iran’s remaining nuclear capacity and future intentions.

The conflict has also strained the broader nuclear non-proliferation regime. Some regional “hedging states” (countries on the threshold of becoming a nuclear power) may now feel emboldened to hide nuclear activity from the IAEA, fearing that transparency may invite pre-emptive strikes rather than international support.

Potential Retaliation and Proxy Risks

Iran’s immediate military response included the launch of 14 ballistic missiles at U.S. bases in Qatar. While intercepted with minimal damage, the act signals the potential for broader retaliation. Homeland Security in the U.S. issued warnings about possible Iranian cyberattacks targeting critical infrastructure, and intelligence agencies are assessing risks of terror proxies attacking U.S. or allied interests globally. Iran may also attempt to race toward building a nuclear weapon — either to deter future strikes or to leverage negotiations from a position of strength. Tehran may have already dispersed fissile materials across the country, to avoid future detection or targeting.

Global Reactions and the Path Forward

The airstrikes risk destabilizing the fragile architecture of global nuclear diplomacy. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), once hailed as a model of multilateral engagement, now lies in tatters. China and Russia, though unlikely to endorse a nuclear-armed Iran, may still respond with increased regional support or arms cooperation as counterweights to U.S. unilateralism. At the same time, these powers have shown little interest in Iran crossing the nuclear threshold. Instead, discussions are emerging about establishing a regional nuclear energy framework with safeguards — a long-term diplomatic solution that might balance access to peaceful nuclear technology with steady monitoring mechanisms.

The 12-day war was not a full-scale conflict in the traditional sense, but rather a demonstration of how precision warfare, cyber strategy, and proxy engagement define modern confrontation. While the strikes have, in the short term, severely hampered Iran’s nuclear infrastructure, the long-term consequences remain deeply uncertain. It must be remembered that a ceasefire is not peace — it is a pause.

What follows will depend not only on Iran’s next move, but on whether the global community can build a diplomatic path forward that prioritizes transparency, non-proliferation, and mutual restraint. Without that, this short war may only be the opening chapter of a longer, more dangerous conflict.