Introduction

At the beginning of August 2025, the United States, under Donald Trump’s presidency, imposed an additional 25% tariff on Indian exports, bringing the total up to 50%, resultant of India’s continued imports of Russian crude oil and its growing alignment with China. This decision came amid rising U.S. domestic political pressure to reassert trade protectionism and penalise non-aligned economies perceived to be undermining Western sanctions on Russia. The escalation specifically targeted sectors where India holds a significant market share and competitive advantage, intensifying concerns across India’s export-heavy industries. These imports and the US’s economic protectionism could also damage indian agriculture, and thus this leads to India holding a firm stand in maintaining its economic autonomy, by taking all actions necessary to protect its national interests.

With the U.S. historically being India’s largest single export destination, accounting for roughly 17% of total outbound trade, the implications are far-reaching. The tariffs span textiles, pharmaceuticals, auto components, marine products, and gems, sectors which collectively employ millions and contribute heavily to India’s foreign exchange reserves. By combining economic coercion with geopolitical signalling, the Trump tariffs have triggered not just economic responses but also a broader recalibration of India’s trade partnerships and foreign policy posture.

1. The Trigger: Energy and Alignment

At the centre of the escalating tariff war between the United States and India lies a strategic disagreement over energy policy and global alignment. India’s decision to significantly increase its imports of heavily discounted Russian crude, now accounting for over 35% of its energy mix, has drawn sharp criticism from the U.S. administration. While India views this as a matter of economic necessity and its own energy security, helping to stabilise inflation and lower production costs across multiple export sectors. However, Washington interpreted it as a geopolitical betrayal, undermining Western efforts to isolate Moscow over the Ukraine conflict.

Trump’s decision to raise total duties on many goods to 50% was not just a trade measure, but as a political message leading to compound tensions. Indian firms linked to Iranian oil were also hit with U.S. sanctions, and there are ongoing threats to expand tariffs into other energy-intensive sectors such as chemicals and refined fuels. The underlying narrative from the U.S. side is clear continued economic engagement with Russia, through oil, may carry consequences far beyond diplomacy. India has not remained silent and strongly criticised in what many analysts see as a valid counterpoint; Indian officials accuse the U.S. and European Union of their hypocrisy. Despite the sanctions, both Western blocs continue importing Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG), metals like palladium, and fertilisers through direct and indirect channels. The global trade order is fragmenting, and national interest and energy security now often override collective alignment and in this context, India is simply acting as any sovereign nation would.

The energy sector has become a flashpoint in this dispute where Indian oil marketing companies (OMCs) face mounting pressure, caught between the need to maintain access to cheap Russian oil and the growing risk of U.S. economic penalties. If forced to cut Russian crude imports, OMCs could face thinner margins and rising costs, which would cause a ripple effect across the economy.

Jefferies has estimated that the trade and energy-related disruptions could trim 0.6 to 0.8 percentage points from India’s GDP growth in the near term. Following this, the U.S. has expressed interest in long-term LNG and clean energy partnerships, meaning that Indian firms with diversified sourcing strategies and investments in renewables may benefit from a reconfigured relationship in the long run.

The pharmaceutical sector, meanwhile, finds itself in a precarious position. For now, Indian pharmaceutical exports to the U.S., primarily generics, have been spared from the tariffs due to their critical role in American healthcare. However, this is under review through an investigation, and the possibility of tariffs as high as 250% looms. If it is imposed, such a policy would cause a severe blow to India’s $8 billion pharma export business. Investors and industry leaders are already shifting focus to firms with robust active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) supply chains and more geographically diversified export markets. Textile industry has also absorbed the sharpest impacts as the 50% tariff has made Indian textile products 30–35% more expensive than those from competitors in ASEAN countries and Brazil. Many exporters, especially small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), have already started to lose U.S. orders due to pricing disadvantages.

According to the Federation of Indian Export Organisations (FIEO), over 55% of Indian exports to the U.S. are now at risk and in response to this, exporters are rapidly pivoting to alternative markets such as Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Indonesia, nations with favourable trade terms and growing regional demand. This shift underscores the importance of flexibility and speed in supply chain operations, especially in globally exposed, labour-intensive sectors. Policymakers are focusing on three fronts that are: diversification, resilience, and diplomacy. Efforts are underway to reduce reliance on U.S. markets by expanding trade ties in Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. There is also a renewed push to strengthen domestic supply chains, particularly in energy, pharmaceuticals, and manufacturing, to protect against external shocks. At the diplomatic level, India continues to engage the U.S. in bilateral negotiations aimed at securing exemptions or balancing concessions in areas such as agriculture and dairy exports.

Ultimately, the U.S.–India tariff dispute is about more than just customs duties or trade balances; it reflects a deeper shift in the rules of global economic engagement. Energy strategy has become a new front line in international relations, and trade policy is increasingly being used as leverage in geopolitical bargaining. For India, the challenge lies in maintaining its strategic autonomy while still integrating with global markets. Navigating this tightrope will require a mix of pragmatism, resilience, and agile economic policy. For investors, businesses, and policymakers alike, the key takeaway is clear that the world’s biggest democracies are entering a more transactional phase in their relationship, one where interests, not ideals, are leading the conversation.

2. Quantifying the Economic Impact

The tariff escalation has sent shockwaves across India's key export industries, many of which are highly labour-intensive and integrated into U.S.-centric supply chains. With $87 billion worth of exports affected, the repercussions are sector-specific and severe.

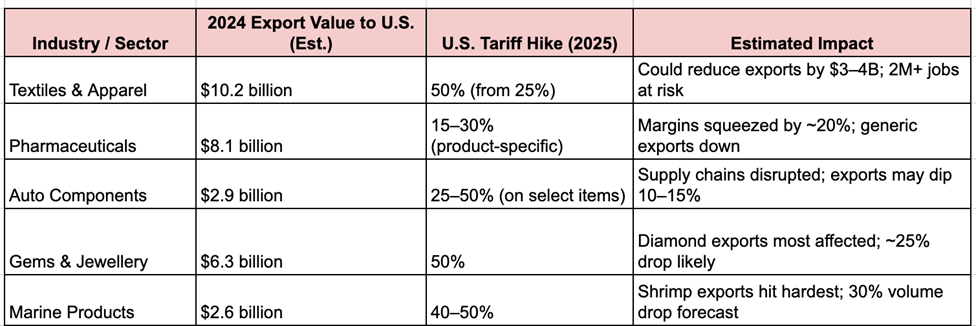

Below is a sector-wise breakdown of estimated exposure, tariff hikes, and economic consequences:

Source : Data derived from Edwin foster- AI invest

This data underscores how the fallout is not uniformly distributed- The U.S. tariff hikes leave India with estimated losses exceeding $7–9 billion annually across five major sectors. Textiles and apparel, India’s largest labour-intensive export category to the U.S. ($10.2 billion in 2024), now face a 50% tariff, potentially cutting exports by $3–4 billion and putting over 2 million jobs at risk, particularly in MSME-dominated hubs like Tirupur and Ludhiana.

Pharmaceuticals, with $8.1 billion in exports, will see margins squeezed by around 20% due to 15–30% tariffs, weakening the global competitiveness of Indian generics, which currently make up 40% of the U.S. generic drug market. Auto components face a 10–15% export decline under 25–50% tariffs on select parts, impacting supply chains and industrial clusters in Pune and Chennai. Gems and jewellery exports ($6.3 billion) are expected to drop by 25% as the 50% tariff hits polished diamond exports hard, affecting artisanal jobs in Gujarat.

Marine products, especially shrimp, are forecasted to suffer a 30% volume drop under 40–50% tariffs, threatening coastal livelihoods and undermining seafood infrastructure in Andhra Pradesh and Kerala. These disruptions have cascading effects on rural employment, export logistics, MSME solvency, and even the rupee, as declining export revenues shall weaken forex reserves and raise import inflation. This looming threat can lead to a global trade diversion as U.S. importers are turning to Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Thailand, almost replicating the 2018–19 U.S.-China trade war pattern. If other western economies replicate these tariffs under political pressure, India could face strategic exclusion from key global markets, reversing decades of export-led growth and putting its broader macroeconomic stability at risk.

3. Trade Theory : Models That Explain the Shift

The Heckscher-Ohlin model, one of the important frameworks in trade theory, suggests that countries export goods that intensively use their most abundant factors of production. In India’s case, labour is an integral and relatively inexpensive resource, which gives it a natural comparative advantage in labour-intensive exports such as textiles, garments, gems and jewellery, leather goods, auto components, and generic pharmaceuticals. This model has historically aligned with India’s trade profile, where the country has served as a major supplier of these goods to capital-rich economies like the United States, which, in turn, specialise in exporting high-end machinery, software, and financial services. However, the imposition of steep U.S. tariffs and raising duties on Indian goods to as high as 50% affects this natural flow of trade. Indian products, once competitively priced due to labour cost advantages, now face price inflation in U.S. markets, diminishing their appeal. Theoretically, under the H-O framework, U.S. firms would respond by sourcing similar products from other labour-abundant countries such as Bangladesh or Vietnam. However, geopolitical realities complicate this adjustment as Bangladesh shares similar labour cost structures and product capabilities, especially in textiles. Its trade relationship with India is burdened by tensions over unresolved cross-border migration issues and growing Chinese economic influence in Dhaka. These strains have led to strategic caution on India’s part, limiting the depth of bilateral economic integration. As a result, while U.S. firms might independently pivot toward Bangladesh as a sourcing alternative, India itself is more likely to diversify toward Southeast Asian economies or deepen trade ties with Middle Eastern partners such as the UAE, where economic complementarities are supported by stronger political alignment. In this way, the Heckscher-Ohlin model’s assumptions are directionally correct but are moderated by real-world geopolitical frictions that determine the actual pattern and pace of trade reallocation.

India’s strengthening economic ties with the Middle East, particularly the UAE, are emerging as a strategic alternative to traditional Western partnerships. Rather than relying solely on longstanding trade corridors, India is now increasingly leveraging regional cooperation to safeguard its economic interests. The UAE–India Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) has already catalysed tariff reductions and expanded bilateral trade, but its true promise lies in fostering long-term, multi-sector integration.

The UAE’s role as a global financial hub synergises well with India’s expanding capital markets, paving the way for cross-border listings, joint venture funds, and startup incubators. Investments, such as ADIA’s $500 million into Lenskart and a $4 billion fund earmarked for future projects, underscore investor confidence in India’s growth story, countering Trump’s narrative about India being a “Dead Economy”. Simultaneously, Indian entrepreneurs like Lulu Group are making major breakthroughs in the UAE markets, including a $1.72 billion IPO in 2024. The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) could further amplify these linkages by supporting collaborative infrastructure development and logistics, but the EU’s integration within this seems difficult due to growing pressure on it from the US. However, unlocking the full potential of this partnership requires India to streamline regulatory processes and ease restrictions that currently deter foreign investment. In contrast to the volatility of U.S.-centric trade relationships, India’s deepening engagement with the Middle East offers a more stable, mutually beneficial pathway, one that aligns with broader efforts to decentralise global trade flows and foster “strategic interdependence” in a multipolar world whilst maintaining autonomy.

ii. Trade Diversion Theory

Richardson’s trade diversion framework underscores how protectionist policies like the recent U.S. tariffs on India redirect trade away from efficient suppliers toward politically favourable but often less efficient alternatives. In practice, the levying of steep duties on Indian exports has made once-competitive industries (textiles, auto parts, pharmaceuticals) economically unviable in the U.S., prompting importers to pivot rapidly toward Southeast Asian hubs. Yet, these shifts are not purely cost-driven, as per Richardson’s concept of endogenous protection, where tariffs are shaped by domestic political objectives echoes loudly here because this U.S. move is as much a geopolitical signal aimed at Russia-linked India as it is economic policymaking.

Interestingly, this diversion can destabilise the so-called ‘beneficiary’ markets too. Al Jazeera reports growing U.S. scrutiny of transhipment routes through Southeast Asia, hinting that what begins as trade diversion may soon turn into broader realignment or secondary targeting. India, instead of passively absorbing losses, is staging its own counter-diversification, channelling trade toward Gulf partners and ASEAN economies where political alignment and supply reliability are stronger. Under Richardson’s lens, the real story is not just about lost exports, but how tariffs catalyse a reshuffling of trade alliances and supply networks, creating both risks and new opportunities in a global economy that's increasingly defined by political rather than purely economic logic.

Meanwhile, Brazil’s President Lula has taken a notably different approach to the tariff fallout, one that underscores the rising geopolitical stature of the BRICS bloc. Rather than negotiating with Washington, Lula has opted to reach out to the leaders of India and China, seeking to coordinate a collective BRICS response to the U.S. tariffs. This move displays not just a defensive stance against protectionism, but it signals a pivot towards solidarity among emerging leaders and economies, turning a corner to shared resilience against the U.S. Under the lens of Trade Diversion Theory, as tariffs coerce market players to shift trade flows, the realignment is influenced as much by political alignment as by economic efficiency, making it a strategic shift. Lula’s embrace of the BRICS framework highlights how nations are now treating trade as both a diplomatic tool and an economic lifeline.

If India's deepening ties with the Middle East and multilateral momentum within BRICS converge, emerging economies may begin shaping new trade corridors less susceptible to Western volatility. In this context, BRICS isn’t merely a trading group, it’s an alternative axis of global cooperation, countering the U.S’s disguised hegemony over the world.

4. Currency and Forex Implications

As of August 1, 2025, India’s foreign exchange reserves plummeted by USD 9.3 billion to USD 688.9 billion, a drop economists suggest to the RBI intervening in forex markets to defend the rupee amid tariff-induced turmoil. This is also India’s steepest weekly slide in nearly three years, with the rupee losing 1.18% against the dollar in that span. The rupee depreciated to ₹87.95/USD, approaching a historic low threshold, but was capped due to RBI support. Early Thursday dates 7th August, 2025- trading saw the rupee bounce to ₹87.69/USD, reportedly due to forward traders having already priced in the tariff shock.

Foreign equity investors are offloading assets at scale, where India saw $2 billion in FII sales in July and $900 million in early August, as markets reacted to trade uncertainty and geopolitical risk. On August 5, net sales across equities and debt exceeded $165 million, amplifying this liquidity pressure. Despite weakened currency and risk-on capital flows, the RBI maintained the repo rate at 5.50%, citing a narrowing global interest rate gap and limited scope to cut further while preserving policy flexibility.

This intervention helped temporarily stem the rupee slide but came at a cost of tighter liquidity conditions, upward pressure on short-term yields, and increasing rollover risk for dollar-denominated corporate debt. Unless India stabilises its trade balance and attracts new capital inflows, continued pressure on reserves may limit future monetary flexibility and amplify macroeconomic fragility.

Conclusion

The Trump tariffs on Indian exports mark more than just a crack in the bilateral trade, but they signal a reordering of global economic dynamics. What began as a targeted response to India's oil diplomacy and strategic neutrality, especially its energy ties with Russia, has escalated into a wider test of India’s resilience in the face of economic coercion.

While the short-term costs like shrinking exports, job losses, and currency volatility are palpable, India’s broader response underscores a pivot from reactive trade dependence to proactive strategic diversification. As traditional Western partnerships grow more transactional and conditional, India is recalibrating its external engagements and deepening energy and defence ties with Russia, expanding commercial corridors with the Middle East, and embracing the BRICS framework as a counterweight to Western protectionism.

This transition reflects a larger global trend, where the decentralisation of trade power and the emergence of a multipolar economic order, where emerging economies no longer remain passive recipients of global policy, but active shapers of new rules, further enables nations to follow strategic autonomy. The tariffs may have triggered disruption, but they’ve also accelerated India's movement toward economic autonomy, political leverage, and a diversified future, where resilience is not just about enduring shocks, but about redefining the terms of engagement altogether.

References:

- https://www.arabianbusiness.com/politics-economics/india-middle-east-can-step-in-to-reshape-global-trade-amid-trump-tariff-war-expert-says

- https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2023/234/article-A001-en.xml

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/8/6/trumps-transshipment-crackdown-spells-danger-for-southeast-asian-economies

- https://www.firstpost.com/india/how-trump-tariffs-are-hurting-the-rupee-clue-lies-in-9-bn-drop-in-indias-forex-reserve-ws-e-13920703.html

- https://cryptorank.io/news/feed/e2ca9-india-brics-relations-wake-up-call-china-offers-better-deal-than-us

- https://www.indianretailer.com/article/retail-business/retail/5-indian-industries-will-be-hit-hard-us-tariffs-2025

- https://www.ainvest.com/news/india-trade-negotiations-assessing-tariff-risks-energy-sector-implications-indian-exports-2508/